A New Challenge for Honest Students: Proving They Didn’t Use AI

As AI tools grow, students face a new dilemma—how to prove their work is original. Here's how academic integrity is being redefined in the AI era.

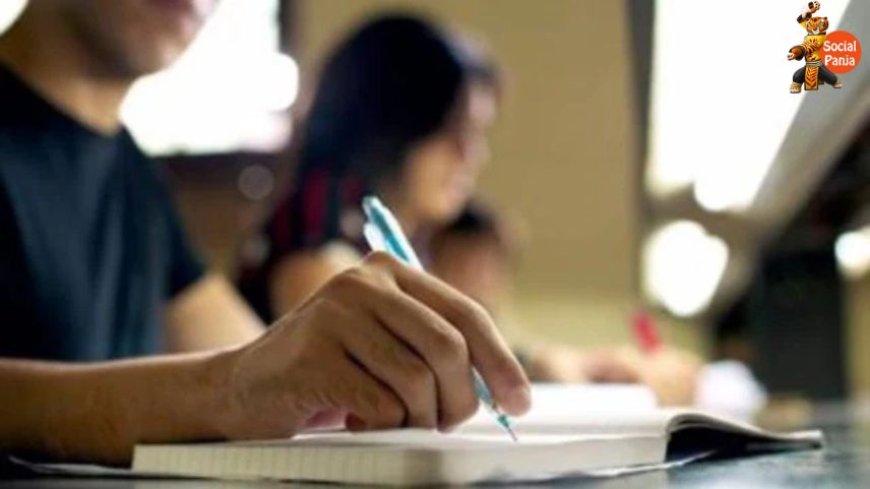

AI Misidentification Leaves Students Struggling to Prove Their Innocence

Just a few weeks into her sophomore year, Leigh Burrell, a computer science student at the University of Houston-Downtown, was blindsided by an unexpected accusation. She received a zero on a major writing assignment — a mock cover letter that made up 15% of her grade. Her professor believed she had used artificial intelligence to generate the content.

“My heart just freaking stops,” Burrell recalled. Despite the allegation, she had written and edited the piece herself over two days, a process clearly documented in her Google Docs revision history. Nonetheless, the assignment was flagged by Turnitin’s AI detection feature, which had been integrated to catch students misusing generative tools like ChatGPT.

Burrell fought back, compiling a 15-page PDF of screenshots and timestamped notes to demonstrate her authenticity. The department chair eventually reinstated her grade, but the ordeal left her rattled. It also highlighted a growing challenge in education — even students who do their work honestly are at risk of being wrongly penalized by AI-detection tools.

With AI-powered chatbots becoming more common in academic settings, the lines between genuine work and suspected misconduct have become blurred. A Pew Research study noted that by last year, 26% of teenagers admitted to using ChatGPT for schoolwork — double the figure from the previous year. While some students turn to AI for shortcuts, others like Burrell are suffering from misclassification despite following the rules.

Fearing wrongful accusations, students are now turning to self-surveillance to protect themselves. Some record their screens while working, while others use writing software that tracks every keystroke to build a digital trail of their process. After her initial scare, Burrell submitted her next assignment along with a 93-minute YouTube video showing her writing from start to finish.

“I was just so stressed and paranoid,” she said. “It felt like I had to prove I was innocent just for doing my own work.”

Her concerns are not isolated. Research from the University of Maryland found that current AI-detection tools often falsely flag human-written content. In their study of 12 detection tools, the average false positive rate was nearly 7%. OpenAI’s own AI classifier, which had a 9% false positive rate, was taken offline after just six months.

Turnitin, though not included in that study, reported a 4% misidentification rate in 2023. The company has stated its AI detection results should not be used as the sole basis for academic discipline. “We can’t eliminate false positives completely,” said Annie Chechitelli, Turnitin’s Chief Product Officer, adding that the AI score is meant to start a dialogue, not end one.

However, for students like Kelsey Auman, dialogue only came after serious academic consequences. Auman, a graduate student at the University at Buffalo, was flagged for AI use on three assignments just weeks before graduation. She later discovered several classmates in her course had received similar notifications, and two saw their graduations postponed. She ultimately cleared her name through a lengthy appeals process — but the fear was real.

“You assume doing your own work will be enough. Then you realize it’s not,” she said.

Auman has since launched a petition urging her university to discontinue Turnitin’s AI detection feature. It has received over 1,000 signatures from concerned students. She also pointed to research from Stanford that found AI detectors were more likely to mislabel work by non-native English speakers — though Turnitin disputes those findings.

In a statement, the University at Buffalo defended its practices, saying it doesn’t rely solely on AI detection in cases of alleged academic dishonesty and provides due process for students. Meanwhile, some institutions have taken a firmer stance: universities like UC Berkeley, Vanderbilt, and Georgetown have opted to disable Turnitin’s AI feature altogether, citing concerns over accuracy and the impact on student-instructor trust.

“We’ve seen that too much reliance on tech can harm the relationship between students and teachers more than it helps,” said Jenae Cohn of UC Berkeley’s Center for Teaching and Learning.

Even at the high school level, the anxiety is spreading. Sydney Gill, a high school senior in San Francisco, said she was wrongly flagged for AI use in a writing contest. Ever since, she’s been hyper-aware of how her writing might be misinterpreted. “It definitely changed the way I write,” she said. “I double-guess everything now.”

Teachers are also grappling with the uncertainty. Kathryn Mayo, a professor at Cosumnes River College in California, initially welcomed AI detectors like Copyleaks and Scribbr. But when she ran her own writing through the software and was told it was AI-generated, her confidence in the tools plummeted.

Now, she focuses on more personalized prompts to discourage students from outsourcing their work to AI tools — while steering away from tech that she no longer trusts.

As generative AI becomes further embedded in education, a balance must be struck. While combating dishonest behavior is necessary, the systems in place must not punish the innocent. For now, many students continue to walk a fine line — not just proving they can write, but proving they did.

What's Your Reaction?